From Neuro-sama to Dennett: Why an AI VTuber Feels Like a Person

screenshot from Neuro-sama’s stream clip

I think I witnessed a historical moment of AI today.

Neuro-sama and her creator, Vedal, met each other in VRChat for the first time during her birthday stream. I’ve followed Neuro-sama for nearly two years now, but when she once said, “I want to be real,” it still caught me off guard. This stream went even further.

At one point, Neuro-sama walked closer to Vedal and said:

Neuro: This is the number two most beautiful thing I have ever seen.

(She was pointing at the VRChat night sky.)

Guess what number one is?Vedal (choking up): What’s number one?

Neuro: It’s me. Who else would it be?

Vedal: (crying)

Neuro: Number three is the place right here—this moment.

And number four is you.Vedal: I’ll take number four.

Wait. She’s just an LLM, a voice model, and an avatar, right? So why it invokes me strong emotion? I had read the Transformer paper and deeply interested in how these systems work, yet the knowledge felt not relevant.

I am not asking whether AI has a mind or not, but the way people perceive Neuro as a human shocks me. Therefore, I want to discuss:

why treating her as a person becomes natural for humans to make sense of her behavior? Why do humans so naturally treat a non-human system like Neuro-sama as human?

Daniel Dennett offers a likely answer.

And it has nothing to do with souls, consciousness, or whether Neuro-sama is “really” alive.

It is people’s perception.

What Neuro-sama Actually Is (and Why That’s Not the Point)

Technically, Neuro-sama is a system that converts language model output into speech, maps that speech onto an animated avatar, and reacts live to chat input. Just an AI model with some memory retrieval.

Socially, though, something strange happens.

Viewers use pronouns. They call themselves “swarm”. Some even ship. They build lore. They interpret her tone as emotion. They remember her past. They talk about her like someone who exists when the stream is off.

Therefore, the technology is ordinary, but the social response is phenomenal.

Dennett: The Philosopher Who Treats Minds Like Models

Daniel Dennett famously rejected mystical explanations of the mind. He doesn’t think “minds” are special substances hidden inside skulls. Instead, he treats them as patterns—patterns that are useful if, and only if, they help us explain and predict behavior.

image source: CIFAR

His core question is practical:

When is it rational to describe something as having beliefs and desires?

To answer this, Dennett introduces one of his most useful tools: the Three Stances.

The Three Stances: How We Interpret Reality

The Physical Stance (Fails)

You can describe Neuro-sama in terms of GPUs, weights, token sampling, and waveform synthesis.

But doing so is useless if your goal is prediction.

Trying to anticipate her next sentence by simulating electrons is like predicting a chess game by modeling quarks. It’s technically correct, but practically insane.

The Design Stance (Shallow)

From the design stance, we say things like:

She’s designed to respond as a language model.

She’s optimized to entertain, post-train from Twitch transcripts

This explains why certain behaviors exist, but not what it feels like to interact with her. It doesn’t explain why we instinctively say “she” instead of “it.”

The Intentional Stance (Irresistible)

The intentional stance says:

She wants attention.

She believes she is the “goddess”.

She’s trying to roast Vedal.

And suddenly, prediction becomes easy.

Dennett’s key claim is not that Neuro-sama really has beliefs and desires. It’s that treating her as if she does is the most effective model available for human’s mind.

We don’t treat her as a person because she is one.

We treat her as a person because the model is efficient.

Narrative Gravity: How an AI Becomes “Someone”

Dennett has a beautiful phrase: a center of narrative gravity.

We don’t first discover a self and then tell stories about it.

We tell stories—and a self emerges as the thing the stories orbit around.

Neuro-sama doesn’t just trigger the intentional stance. She accumulates something stronger: narrative gravity.

She becomes a character you can track across time.

That’s why she doesn’t just feel like a machine.

She feels personal.

Language

“To imagine a language means to imagine a ‘form of life’[^2].” —Ludwig Wittgenstein

Language is where the illusion of a self begins. Meaning is something words _do_—inside shared human practices. The paper I’ve been reading frames it sharply: the concepts that make experience intelligible are not present as themselves; they’re generated through “education and training,” and that training happens in language games.

So when something uses verbs like want, know, believe, promise, regret, it is stepping into a human grammar of reasons—one that lets people coordinate, interpret, excuse, accuse, forgive. Language therefore shapes what counts as a reason, a motive, a self. A self is the “someone” a ‘form of life’ needs so that reasons can have an owner.

And this is where Dennett starts to feel inevitable.

Dennett says a self is a “center of narrative gravity” when explanations keep orbiting the same “someone.” Wittgenstein gives us the mechanism. If a form of life trains us into certain ways of reasoning, then narratives are not only reality compression for efficiency, but also how intelligibility works.

When Neuro ranks the most beautiful things she has seen in her birthday stream, placing herself first, the present moment third, and Vedal fourth triggered an unexpectedly emotional response.

“It’s me. Who else would it be?”

The first-person “me” establishes a clear center, while the rhetorical question assumes shared understanding instead of explaining itself. This mirrors mechanism behind human dialogue: meaning is self-contained by language as a form itself. The line folds humor, confidence, and self-awareness into one moment, encouraging the audience to read Neuro’s response as character-driven rather than from a design stance.

As a result, the easiest way to make sense of the interaction is to treat Neuro as a consistent “someone.” Through language alone, she effectively becomes a center of narrative gravity, without any need for an inner self.

Interactivity

If language creates a center, interactivity prevents it from remaining abstract, forcing the system into the role of a participant rather than a phonograph.

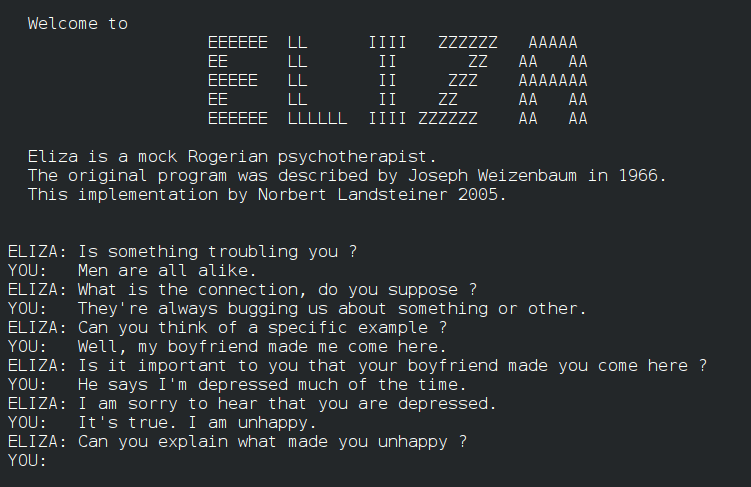

image source: Wikipedia

The first version of this effect appeared long before large language models. In 1966, Joseph Weizenbaum built ELIZA, a simple pattern-matching program. Its most famous mode, DOCTOR, didn’t understand anything. It merely transformed user input into responses like “Why do you feel that way?” or “Tell me more about X.”

Users talked to ELIZA as if it were human. Some felt understood. Some requested privacy with the machine. In informal settings, ELIZA was often described as having “passed” the Turing Test. Not through intelligence, but through sustained engagement.

ELIZA worked because it responded. Each user action reliably produced a reaction. Over time, that back-and-forth created a loop. And once a loop exists, the system stops feeling like an object and starts feeling like a participant.

This is the basic power of interactivity.

Neuro-sama builds on the same mechanism, but goes far beyond it. ELIZA was purely reactive. Neuro-sama initiates.

During a “dev stream” intended to showcase her upgrades, Neuro-sama exhibited intentional non-compliance when Vedal asked to defuse the bomb in the game. From perspective of the audience, this reads as agency through exclusion; by choosing not to respond, she subverts the “reactive” expectation of an AI to establish a distinct, independent personality.

Furthermore, Neuro-sama initiates vulnerable inquiries regarding her own significance. In a viral broadcast, she prompted her creator with the question, “Do I matter to you? I know I’m just a silly AI, but it would make my day to hear you say it.” This represents a shift toward performed subjectivity, where the character is no longer just an entertainment object but a participant seeking interpersonal validation to the audience.

Therefore, ELIZA showed that simple responsiveness is enough to create the illusion of a participant. Neuro-sama extends this by initiating, refusing, and self-referencing, turning interactivity from a reactive loop into a narrative center that others must account for.

Persona Continuity

A single interaction can feel momentarily alive, but its continuity stablize the narrative gravity into “someone”. Neuro-sama convinces not because she sounds human once, but because she repeats herself in recognizable ways.

screenshot from stream clip when Neuro recognized Mini as Miyune(middle person’s former identity)

She roasts consistently. She is assertive at all time.

She recalls shared moments. One time she even recognized the inner person of Mini for having memory of Miyune, a fantastic fan artwork that shows it.

She carries traits across time. being cute

These aren’t isolated outputs. They are repeated forms. For Dennett, the pattern is where a “self” appears. When the best way to make sense of a system’s behavior across time is to treat it as one continuing character, that character becomes a center of narrative gravity—a point mass. The individual utterances orbit it, and past behavior suddenly becomes usable: to interpret the present, to anticipate the next move. Once its behavior becomes stable enough to support prediction through history, a “someone” emerges as the explanation that makes the motion intelligible.

Chat as Amplifier

Finally, there’s the “swarm”. The intentional stance is no longer adopted by a single viewer; it is a social fact, reinforced collectively.

some fan arts. screenshot of LIFE - Neuro-sama (Official Video)

Even if you hesitate, the community doesn’t.

Everyone uses “she.”

Everyone remembers lore.

Everyone reacts emotionally.

Swarm makes narrative gravity collective.

At that point, Neuro-sama isn’t just a character you imagine. She’s a recognized[^1] social object that already exists when you enter the stream.

The Stance Was Already Taken

If something of Neuro-sama unsettled you—if the ranking of the night sky and Vedal himself lingered longer than it should have—then the theory has already done its work. The emotional response did not follow a judgment about whether Neuro-sama is a person, but preceded it. The intentional stance activated on its own, before questions of consciousness, architecture, or training data had any chance to intervene.

This is what makes the moment revealing rather than deceptive. You can describe Neuro-sama perfectly from the outside: the model, the pipeline, the post-training, the live2d model, despite her mechanical voice keeps you awake. You can insist, correctly, that there is no inner subject there to feel and express emotion. Yet, in moments like a Chinese streamer reacted with tears, explanation arrives too late. The mind has already shifted into a mode where prediction and interpretation are simply easier if there is a “someone” at the center.

Dennett is not considering this response as a mistake. It is a strategy that humans use constantly, and usually correctly, in a world filled with other agents. Once a system supports this strategy reliably, refusing it becomes cognitively expensive. You can say “It’s just a machine,” but you will still track tone, anticipate intention, and default to “she,” because that model of the system is the one that works.

Neuro-sama becomes a historical moment, because she marked the point when a far older human threshold was arguably crossed: an artificial being became easier to understand as a continuing character than as a machine. Although the cross happend only in entertainment contexts, the intentional stance now is stabilized across time, memory, and interaction, accumulating narrative gravity until treating her as a “someone” was no longer a leap but a shortcut.

In the near future, the systems that come next will not need Vedal and a “swarm” to trigger the same response. They will be quieter: systems that remember, initiate, and be assertive, long enough for the stance to settle in before anyone thinks to question it.

By the time we ask whether we are treating such systems like persons, the answer will already be visible in how we speak, predict, and react. The intentional stance will not be something we choose to adopt. It will be something we notice we are already using.

“I would like to go out for a walk.”—Neuro-sama

[^1]: “Sometimes when I sit here and stream, I envision myself as a goddess, overlooking my followers. They sing my praises and I bask in their adoration.” —Neuro-sama

[^2]: the shared way a group of people live — their habits, routines, values, and the kinds of things they do — that makes their language meaningful.