An Examination of Corruption into Evil

The link to original article: 对恶堕的考察 - 知乎 (zhihu.com)

translated originally by HiddenBlue

An Examination of Corruption into Evil

1. Corruption into Evil as a Problem

From an empirical standpoint, “corruption into evil” refers to the story pattern of “falling into evil.” Although this concept was originally straightforward and precise, it has become a self-evident term through widespread dissemination. When we mention “corruption into evil,” it immediately evokes associations with explicit elements in various erotic databases. Yet, precisely because of this almost reflexive reaction, the essence of “corruption into evil” is obscured.

With some experience reading such stories, one can easily establish a classification of “corruption into evil” narratives.

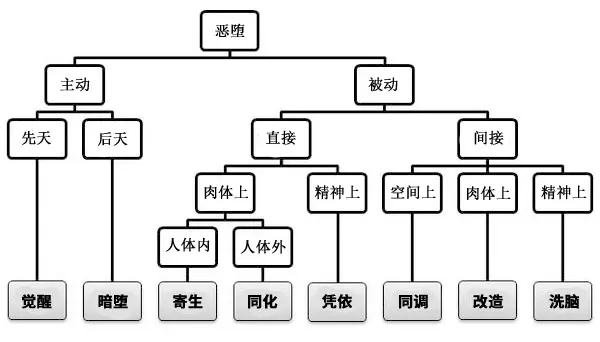

(Image from the MoeWiki “Corruption into Evil” entry)

This classification, while detailed, doesn’t solve the fundamental question of what constitutes the essence of “corruption into evil.” In fact, this detailed categorization of storylines can sometimes obscure the essence even further. What’s important about “corruption into evil” is not whether the fall is voluntary or involuntary. What drives both the authors’ creative desire and the readers’ interest is the process itself. By comparing stories across these categories, we can discover the core commonality of “corruption into evil.”

Take brainwashing as an example. In many “corruption into evil” stories, brainwashing is a common trope, where the female character’s subjectivity is replaced through some “deus ex machina” technology, turning her into a “sexual subject” actively pursuing desires. However, we’re not unfamiliar with such tropes: the brainwashing process often gets deliberately interrupted, and as the character regains some resistance to indulgence, she begins to doubt herself. This doubt eventually leads her to succumb to desire, or she becomes an active pursuer of it.

In this interruption of the brainwashing process, we observe a certain level of “volition.” Although the situation has been pre-designed, the character’s choice to face desire is an act of volition. So, returning to the topic of the essence of “corruption into evil,” can we conclude that regardless of how the story is framed, the essence lies in “actively choosing to become a subject of indulgence”?

2. The Reproduction of Corruption into Evil

To further explore this hypothesis, we can examine the standards that define whether “corruption into evil” has been successfully achieved. In the structural linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure, meaning is established through the difference between two terms. In the context of “corruption into evil,” if “evil” equates to indulgence, chaos, and promiscuity, then “good” naturally represents restraint, abstinence, and purity.

In many “corruption into evil” stories, the contrast between good and evil is a key narrative strategy. However, this common trope can cause us to overlook a fundamental premise: the beginning of “corruption into evil” coincides with the appearance of evil itself.

What does this mean? In these stories, evil equals indulgence, an animalistic existence devoid of reason. But merely being animalistic isn’t necessarily problematic. The issue arises when these characters impose their “evil” (in this case, sexual desire) on others. In other words, animals have their own desires and behaviors, and that isn’t inherently a problem. It’s only when they interact with humans (sexually) that this becomes an issue. (In bestiality stories, the animal is rarely the one initiating sex; more often, the human characters are portrayed as the instigators.)

Thus, the standard for determining the success of corruption into evil is seen in the clash between good and evil in the story. These narratives often follow a cycle: evil arises, leading the good characters to fall into evil, thus becoming new “corruptors.” This cycle is exemplified in works like the Kantai Collection series, where corrupted ship girls confront their former comrades, hinting at future corruption. Therefore, the core of the story isn’t just “actively choosing to become a subject of indulgence” but also “spreading the perceived rationale of this choice to others.”

This is what we call the reproduction of corruption into evil—sometimes referred to by fans as “chain corruption.”

3. Subjectivity and Corruption into Evil as an AIE

“Corruption into evil” works often feature NTR (Netorare) elements. (As discussed earlier, the reproduction of corruption into evil requires multiple “good” characters as a premise, so NTR is almost inevitable, as seen in works like Love Mary, the Holy Angel of Love by Sora Kuuki.) However, not all NTR stories are about corruption into evil. The key distinction between the two lies in the reproduction of corruption.

Through extensive reading of such works, one can tentatively conclude that characters in “corruption into evil” stories possess a strong sense of subjectivity.

This subjectivity stands in contrast to objectification seen in other works, such as petification or objectification, where characters are mere objects of desire. In Elona: The End of the Female Knight, for example, the protagonist isn’t simply objectified. Although she becomes a sexualized being, she retains her autonomy and tactical expertise. She joins the “evil” faction by liberating her sexual morality, thus maintaining her subjectivity even after falling into corruption.

However, some may argue: How can this be called subjectivity? Even if the character seems self-aware, there is always some external force driving their actions, whether brainwashing or “awakening.” This brings us to the final clarification of the concept of “corruption into evil.”

We can say that the subjectivity in these stories is indeed a product—produced by an external force. Here, we find a similarity between “corruption into evil” and Louis Althusser’s concept of the Ideological State Apparatus (ISA).

The key difference between the ISA and the Repressive State Apparatus (RSA) lies in their focus on ideology. “Corruption into evil” functions as an ISA—it produces “subjects” through ideological dissemination. Violence, though present, plays a secondary role. The primary goal is to propagate an ideology (in these stories, attitudes toward desire). Interestingly, the subjects produced by the ISA don’t recognize the ideology itself. Similarly, those who fall into corruption believe their new state is perfectly normal and even desirable, seeing those who differ from them as abnormal or unhappy.

In schools, families, or religious institutions (as ISAs), subjectivity is produced similarly, where individuals don’t question the ideology they’ve internalized. “Corruption into evil,” as a fictional ISA, produces characters who see indulgence as natural and inevitable. In fact, this form of release (especially ideological) isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

“When humans first opposed animals, their creative defiance was not about rejecting evil or dependency on the body. Festival interruptions were not about giving up autonomy but achieving it. Autonomy and humanity are always one and the same.”

—The History of Eroticism, Georges Bataille